Last week, we looked at the important role that philanthropy plays in a vibrant economy. It recycles wealth, creating new opportunity. But philanthropy’s economic power is only part of the story.

Massive philanthropy, after all, comes from massive wealth—and the power that comes with it frequently scares the public. Even back in Rockefeller’s days, the country aligned itself against his effort to create a foundation. That distrust of wealth continues today. Philanthropic villains still get regular coverage, like the Koch brothers by the left, and for the right, George Soros.

In his book, Just Giving, Stanford sociology professor Rob Reich makes a case that large-scale philanthropy poses a risk to democracy itself. Are the concerns justified? Perhaps.

There are two dangers we need to see more clearly.

Perpetual and Unaccountable

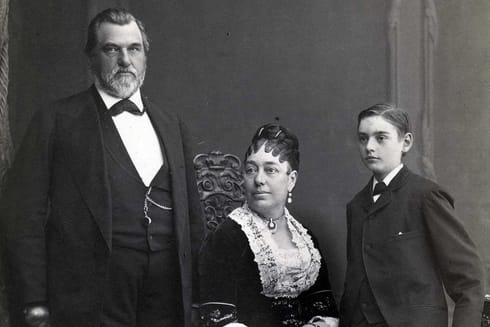

Andrew Carnegie famously noted in The Gospel of Wealth, “The man who dies thus rich dies disgraced,” illustrating that wealth locked away is wealth put to waste. Yet today, most private foundations spend an average just above 5% of their total assets. Because their investment returns are consistently higher than their grant making, this spending level allows them to survive in perpetuity at the cost of accomplishing far less. Perhaps Carnegie might have called a foundation that never even dies similarly disgraceful.

How does foundation frugality affect democracy? As Reich points out, private foundations also lack a great deal of accountability. Certainly they must act within the boundaries set by the tax code, but they don’t have any other market mechanisms to ensure the beneficial use of their resources. Companies of equivalent size have customers to hold them to account. A private foundation has no customers, nor any stakeholders other than the ones they choose for themselves.

And like wealth generally in the US, foundation wealth is concentrating to a smaller number of foundations. So as foundations continue to aggregate wealth and the power that comes with it, they wield even greater power over issues of public policy, like education, crime, and the environment. A community with fewer resources than a large foundation might find itself with little recourse other than hoping for benevolence and wisdom from a board of directors.

Professionalized Decay

Another philanthropy expert and critic, Bill Schambra, has noted that professional philanthropy, the kind characterized by the largest foundations, comes with a poisoned promise: The public need only provide their support, and the professionals can do the rest.

The danger here is that democracy is rooted in people feeling empowered to solve their own problems. I’m tempted to quote at length from a compelling speech Schambra gave on the subject, but I will cut to the chase. After describing the messy, but essential nature of communities crafting solutions, Schambra says:

Furthermore, and more important, by employing experts to undertake the tasks of democratic government, we’ve relieved citizens of the need to engage with each other and to work out their differences in their own messy and amateurish ways.

That can only spell the end of democratic self-governance.

So the other democratic danger in big philanthropy is to our self-efficacy, which we lose by handing our problems over to the experts. Certainly we should involve them and listen to them, but we should be putting our own hands and minds to work on these problems, not just the ones offered—as helpful as they are—by Bill and Melinda Gates.

What can be done about these dangers? Schambra’s advice resonates here:

There is nothing quite like seeing citizens coming into the first realization of their own agency, and living into their ability to control their own lives.

American civil society has over the centuries been the arena within which everyday citizens come to realize their own democratic agency, no matter how marginal, neglected, or oppressed they may otherwise have been in this imperfect democracy of ours.

It is no one else’s job to solve the problems around us. We can turn to others for help, but it’s our own work to do.

Seeing Good at Work

Turning traditional philanthropy on its head, The Philanthropic Ventures Foundation empowers communities through innovative grants that are designed to be small, simple, and fast. The founder, Bill Somerville, pioneered this “grassroots philanthropy” (also the title of his book) by simply taking faxed, one-page applications from teachers looking to better serve their students.

If you want to learn more about their work, I encourage you to watch this fantastic TEDx talk by Somerville. It’s one of my favorites.

Promotional Stuff

That talk by Bill Somerville was delivered at TEDxBYU. This year’s event is entirely online, with incredible speakers filmed in remarkable locations. It runs tonight and tomorrow night, so be sure to get tickets right away. Find out more at: