What your enemies reveal about you

Mirrors are a paradox. They show you an exact opposite of yourself, while at the same time presenting something that is your perfect similitude. You in every way, but the inverse of you.

In a similar way, I’m coming to see enemies as mirrors. The people I choose as my enemies—and I do believe that I’m the one choosing them—reveal my own contours and features just like a reflection does. I think of them as opposite to me, but they reflect back so much about who I am and what I value.

Thinking of our enemies as our opposites, we might take pride in the comparison. If they’re godless, that makes us God-loving. If they’re cruel, that makes us kind. If they’re foolish, that makes us wise. But does this description match the reflection?

If our enemies are judgmental, are we then fair-minded? If they’re quick to offense, are we magnanimous? Hardly. And what’s worse, we might reflect opposition to whatever is good in them. If I set myself against people who love their families, who help their neighbors, and who trust their friends, what does that say about me?

The prickly truth is that you can know a person almost intimately if you discover their enemies. Consider just how reliable that measure is. “Who are your enemies?” would be the ultimate get-to-know-you question for parties and dating apps if it weren’t so miserable to ask.

Last, the enemies we choose don’t make us good any more than a mirror makes us beautiful. It takes more for me to become a good person than just deciding whom I oppose. If our enmity holds our attention, like Narcissus staring at his reflection, then we’re trapped by our own self-regard. It’s sad that we all know someone imprisoned in enmity.

Has anyone ever found real happiness in a mirror? I might have done a few times after a good haircut (back when I had much hair). But there’s nothing there in the mirror that’s real enough to obsess over. If I look away from enemies/myself, I discover whole world of joyful people that I might be lucky enough to call friends.

Things to Read

Joy Generator

NPR's delightful Joy Generator is a great way to spend a few minutes on the Internet. Guaranteed to flight the blahs and cultivate some joy.

Americans, Can You Answer These Questions?

US citizenship tests used to be written and administered by individual judges. They weren't easy. How would you have done?

What Deadlines Do to Lifetimes

"We might be asking too much of individuals by heralding time constraints—one of the most potent currencies capitalism has for perpetuating itself—as moral guides."

Impact Highlight

US veterans who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan wrestle with huge personal costs for their service. Around half of them struggle with one or more of the following: traumatic brain injury, PTSD, anxiety, depression, substance abuse, or anger management. Considering the 2.7 million that have served, the consequences have been massive.

Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America works to provide the veterans of this generation with critical services. Currently serving over 450,000 members, the IAVA has a range of programs including advocacy, VA reform, and education. Their new Quick Reaction Force responds to the most urgent needs of veterans, like eviction or mental health crises, helping to avert disasters for thousands of service members and their families.

Promotional Stuff

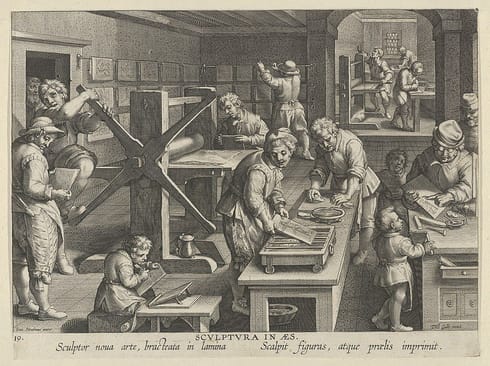

We are surrounded by the fruits of human creativity and innovation. This capacity to improve our world has done immeasurable good. But where does innovation come from and how do we get more of it?

Looking back to one of the most potent periods of world history, my guest this week—Dr. Anton Howes—guides us through the lessons we can learn from the British Industrial Revolution and how those lessons reveal the nature of innovation today. His concept of an "improving mentality" cuts across all of our everyday experiences, and shows us how we can improve our lives and the lives of those around us.